OBJECTS IN 3D

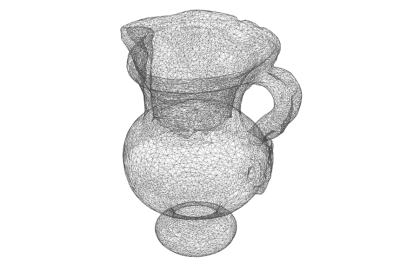

MAJOLICA FROM THE ETHNOGRAPHIC COLLECTION OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM UŽICE in 3D

To view the model on a computer, the mouse commands are: left button to rotate, wheel to zoom, and right button to scroll. The keyboard commands are: cursor keys to rotate, PageUp and PageDown keys to zoom, Shift key + cursor keys to scroll.

About majolica from our ethnographic collection

During the execution of municipal works in Heroja Dejovića Street in Užice (today Nikola Pašića Street), near the National Museum, in 1974, and then in 1982, a total of five hoards of dishes were discovered. The first find contained Italian majolica jugs and a large number of porcelain and ceramic bowls, placed in a large copper pot. Not far from that location, a find with dishes made of Turkish and Italian majolica was later excavated; it, like the remaining finds from that excavation, also contained copper dishes. This dish, which certainly belonged to a Turkish house (the Serbian inhabitants of Užice only acquired significant wealth during the time of the Principality of Serbia), was probably buried in one of the Turkish retreats from the city during the Austro-Turkish wars in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Majolica, or faience, is a type of pottery popular in Europe since the late Middle Ages. Majolica is named after the Spanish island of Mallorca, which was once the largest distribution center for this type of pottery. The name faience comes from the name of the city of Faenza in northern Italy, which was one of the most important centers for the production of majolica-type dishes. Painted and glazed, majolica, like porcelain, was made of white kaolin clay. It sought to achieve the fragility and shine of porcelain, which until the early 18th century was made only in China. Porcelain bowls found in 1974 were, in all likelihood, made in China for the needs of the Turkish market, where, as in all of Europe, the demand for porcelain was high. In the workshops of Iznik (formerly Byzantine Nicaea), not far from Istanbul, blue-and-white majolica has been produced since the 16th century, modeled on Ming dynasty porcelain. However, Iznik craftsmen soon became famous for their majolica vessels of refined form and a wider range of colors, which represented the highest level of Turkish ceramics.

Majolica dishes were highly valued in Italy since the early Renaissance, and in the 17th century they acquired the characteristics of mass production in the workshops of Italian cities. In addition to local characteristics, this hand-painted majolica was distinguished by the freshness of colors and decorative patterns that sought models in Italian painting.

The jugs from the Užice Museum found in 1974 are most similar to Deruta majolica (Deruta – a city in Umbria). Low-footed and spherical in shape, they are covered with a decorative scheme in the form of Raphaelesque, inspired by Raphael’s wall paintings in the Vatican Stanzas. On a milky white background, reminiscent of the shine of porcelain, these Raphaelesque are made of a network of floral elements and representations of real or fantastic creatures.

In Serbia, majolica has been known since the Despotate era, as evidenced by frescoes, while post-Byzantine paintings, in addition to majolica, also depict contemporary Turkish tableware. However, with the arrival of the Turks, luxury imported goods became increasingly difficult for members of the impoverished domestic elite, who increasingly relied on the products of local potters. Serbian craftsmen adapted to Ottoman design patterns, but also to contemporary European experience. During the 18th century, the power of the Turkish Empire weakened, and at that time the influence of European baroque and rococo was noticeable in Ottoman art and decoration; at the same time, the influence of orientalism was felt in the works of European masters.

3D model creation: Sreten Vuković

Text: Katarina Dogandžić Mićunović

Photos: National Museum Užice